Free Your Brain, Free Yourself and Become a Better Professional

TL;DR for my org-roam configuration, jump to Setting up a Zettelkasten in Emacs or checkout my Emacs configuration in Github. For a practical use case jump to Putting it all together.

This article is not an in-depth look at the Zettelkasten method. For a proper explanation there’s no better source than https://takesmartnotes.com.

Any creative activity requires thinking. Lucky for you, your brain is very good at it. Even if you don’t consider yourself a creative person, if you (like me) work in software, programming definitely qualifies as a creative activity. Then you are paid to think.

The problem is that even though your brain is very good at thinking, making connections and coming up with new ideas, unfortunately it’s not very good at objective storage of information. In addition to our poor ability on objective recollection of facts, our short term memory is very limited. The way I picture it is a sort cache: very fast memory, but limited.

Knowing the strengths and limitations, and a little insight on how your brain works, allow you to make better use of it. Play to its strengths.

Note taking frees your brain

Have you ever been so absorbed by a thought or a problem that you couldn’t sleep? What’s happening is that the facts that make up your reasoning about that problem are being kept in short term memory. You’ll ruminate about it until it is done.

But here’s the kicker: the definition of done for your brain is not the same as yours.

Think about this: what would you do in order to “take that thought off of your mind” so you can finally get some sleep? Would you get up and finish the task? Maybe, if it’s possible. But what if that’s not an option? Perhaps you’ll take a quick note, or record a voice memo.

The mere fact of writing the task down “frees” our brain, as it considers the task “done”. Ideally you should be able to continue your train of thought from the note you wrote down though.

That’s where a systematic approach to note taking comes into play.

Build a lattice of knowledge

Fortunately for us, there’s already a systematic approach to note taking, so we don’t have to reinvent the wheel here. Remember: it’s not only about taking notes, but equally important is to recall the facts, continue your train of thought and ideally connect seemingly disjointed facts and build new insights.

The method is known as Zettelkasten. The gist of it is:

- When reading, do it with pen and paper or any other mechanism to record throwaway notes.

- Take the throwaway notes and develop fully fleshed notes that will go into the slip-box. These should be “translated” in your own words, and integrated with the rest of your knowledge base. Think about the insight it provides and how it relates to other notes already recorded. This step should be done in no more than a day, to avoid forgetting important context.

- Review your slip-box. What new insight it provides? What else you need to research? Where are the holes in your arguments? What new path will you take from here?

Repeat these three steps enough, and you’ll end up with a lattice of knowledge. A sort of Neural Network that you can have a conversation with, and helps you think.

(not needing) Willpower

As with any other method, it’s only as good as the effort you put into. The typical advice here goes something like: if you want to reap the benefits of improved thinking and a source of new insights and original ideas, you need to put in the time taking throwaway notes, “translating” them and coming up with their relationships.

In other words, you need willpower.

Willpower, however, is a limited resource and it depletes quickly. You might be off to a good start, being diligent with your note taking and developing your lattice, only to lose interest later and revert back to your old habits.

That is why it is not having willpower that is important, rather not having to use willpower what matters.

I’ll show you in the next section how to setup everything in order to reduce friction and use your computer as a Zettelkasten, one that you can interact with as simple as possible. While the setup might seem complex initially, it’s important to note the purpose: not having to use willpower.

If you need to open up a specialized application, navigate some menus, log in to some Web application or similar, chances are you will stop using it. More so, if you depend on a proprietary application or closed format, you are binding yourself to the fortunes of a third party.

Make your Zettelkasten yours. And that means making sure you own the files, that they are forever readable independent of the software that was used to produce your notes.

Zettelkasten software

There are many software based Zettelkasten tools:

- Zkn3 is free and open source, available for Windows, Mac and Linux. It’s implemented to emulate the physical slip-box (that’s what Zettelkasten means in German) where the note taking method takes its name.

- Zettlr is a markdown editor that can be used to link notes together. It’s free, open source and cross platform (Electron based).

- The Archive is Mac only paid, closed source software. On the bright side, it uses plain text files as storage.

- Roam Research is Web based, with a paid plan. Apps are coming soon. Nevertheless it has taken the note taking community by storm (or so it seems).

- Org-roam is free and open source, available for Windows, Mac and Linux. Uses plain text files and comes with an advanced editor (Emacs). Not so easy to use.

It’s no surprise that I chose Org-roam as my Zettelkasten, but let’s see all of the options above compared:

| Name | FOSS? | Platforms | Cost | Native binary | Plain text? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zkn3 | ✔ | Win, Mac, Linux | Free | ✔ | ✔ |

| Zettlr | ✔ | Win, Mac, Linux | Free | X (Electron) | ✔ |

| The Archive | X | Mac | 20.00 USD | ✔ | ✔ |

| Roam Research | X | Web based | Subscription | X | X |

| Org-roam | ✔ | Win, Mac, Linux | Free | ✔ | ✔ |

You can see how, according to my requirements of making it yours (future proof, not dependent on third party services, open formats) and making it always accessible, Roam Research is the worst. Not only is it software that you don’t own, but you have to open up a browser, log in to their website, and finally create notes. If their service is having issues at the time, or you are in an unreliable Internet connection, you either can’t take notes or risk losing data.

Nevertheless it has captured many people’s attention. I’m sure it has a very polished UI and neat features, and I’m not trying to demerit their work.

Hopefully you are now convinced of the benefits of using a systematic approach to note taking, and are wondering how to set everything up in order to implement the Zettelkasten method with free software that runs natively in your computer and uses plain text as storage format.

Setting up a Zettelkasten in Emacs

Org-roam leverages Org Mode as much as possible. This is great, as there’s a whole ecosystem built around Org Mode that goes beyond note taking and Zettelkasten. For example this blog post was authored in Org Mode and then exported to Hugo.

Not only that, but by becoming proficient at Org (and Emacs) you’ll gain experience in an invaluable tool that can assist you in several other areas such as personal organization, programming, writing, reproducible research, and more. It will make you a better professional.

We will leverage three packages for Emacs: org-roam, roam server and deft. Only org-roam is strictly needed.

org-roam

Org-roam leverages Org Mode as much as possible, only adding the bits and pieces necessary for efficiently implementing a Zettelkasten workflow. It uses the same link mechanisms, and you can use the full power of Org Mode in your Zettelkasten notes.

To install it, with use-package:

(use-package org-roam

:hook (after-init . org-roam-mode)

:config

(setq org-roam-db-location "~/Sync/Org/org-roam.db")

(require 'org-roam-protocol)

:custom (org-roam-directory "~/Sync/Org/roam/")

:bind (:map org-roam-mode-map

(("C-c n l" . org-roam)

("C-c n f" . org-roam-find-file)

("C-c n g" . org-roam-graph)

("C-c n c" . org-roam-capture))

:map org-mode-map

(("C-c n i" . org-roam-insert))

(("C-c n I" . org-roam-insert-immediate))))

By hooking to after-init we make sure we always load

org-roam-mode. Org-roam uses a sqlite database to keep track of

the links and backlinks among notes. By hooking to after-init we

make sure that we always have the latest version of your note links,

even if they were edited outside of Emacs.

org-roam-modewill add significant amount of time to your Emacs startup. I mitigate this issue by running Emacs as a daemon, but it might not be possible in your case. Feel free to remove the init hook, but remember to always startorg-roam-modebefore working with your notes.

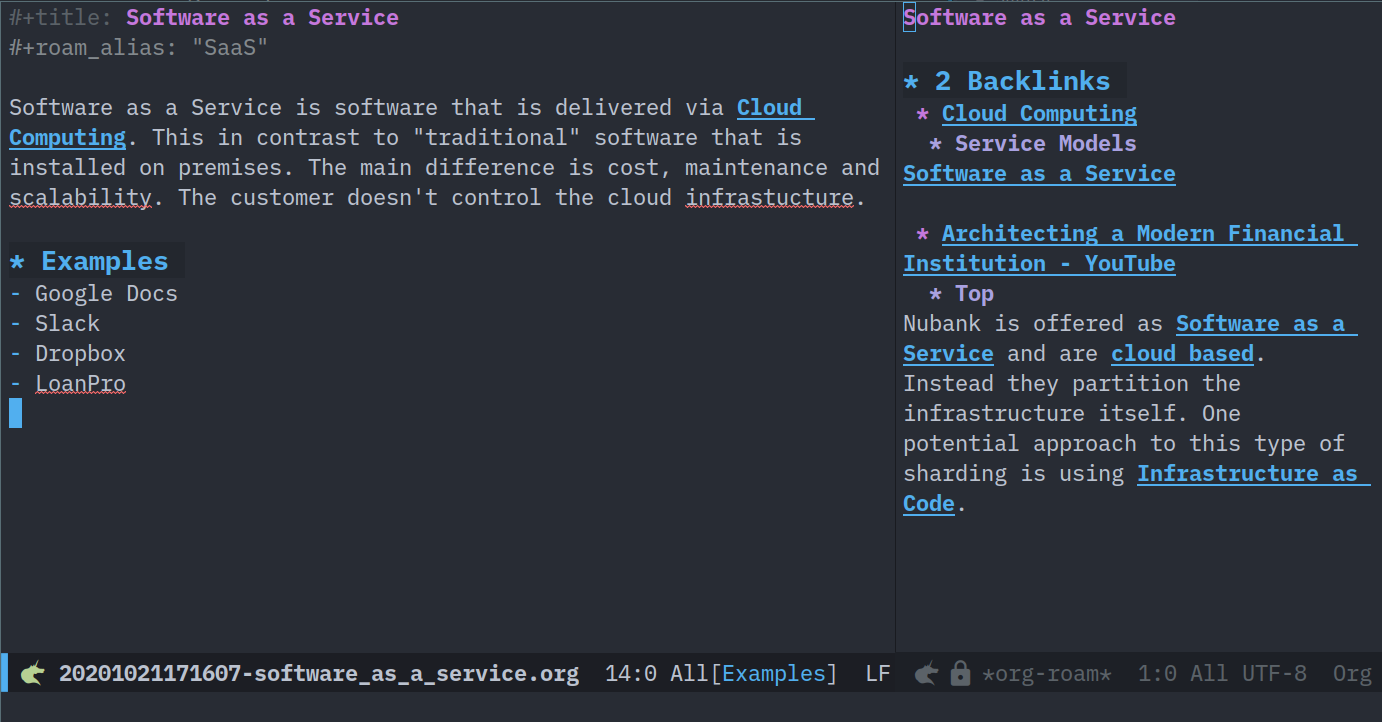

One of the main features of Org-roam is the sidebar, accessible by

visiting a note and executing org-roam. The sidebar will show you

the backlinks, that is those notes that link back to the current

note, along with some context. This is very powerful as you not only

know other related notes, but in what context they relate to each

other. It helps you think about potential connections. You can also

navigate back and forth using the sidebar.

The org-roam sidebar

In the sidebar screenshot, a note called “Software as a Service” is viewed. The note is referenced (backlinked) by other notes: “Cloud Computing” and a note about a YouTube video on “Architecting a Modern Financial Institution”. What’s interesting is the context around these references. For example in the video, it talks about a strategy around sharding the infrastructure; not exactly about Software as a Service, but related nonetheless.

Other commands include org-roam-find-file to quickly finding and

opening a note, org-roam-insert to insert a link to an existing note

while editing a note, and org-roam-capture to create a new note.

Roam Protocol

This is not a separate package, but a functionality that is built into org-roam. The purpose of this configuration is twofold:

- So that you can click on a graph node, and have it open in Emacs with the corresponding node in view.

- So that you can create a new note straight from your browser, for example when reading an article or playing a video on YouTube.

The instructions for this setup depend on your OS and browser, so I won’t replicate them here. Just go to org-roam’s manual and follow the instructions. I wholeheartedly recommend that you do so though, as it lowers the effort barrier (no Willpower required!).

Org roam server

Org-roam comes with the ability to graph your network of notes (your knowledge lattice). I find this extremely useful, and the best way to navigate your notes and find interesting insight.

However the graphing solution in plain Org-roam is serviceable, but there’s a better one: Org-roam-server. This nifty piece of software creates an interactive graph that you can view in your Web browser.

(use-package org-roam-server

:config

(setq org-roam-server-host "127.0.0.1"

org-roam-server-port 8080

org-roam-server-authenticate nil

org-roam-server-export-inline-images t

org-roam-server-serve-files nil

org-roam-server-served-file-extensions '("pdf" "mp4" "ogv")

org-roam-server-network-poll t

org-roam-server-network-arrows nil

org-roam-server-network-label-truncate t

org-roam-server-network-label-truncate-length 60

org-roam-server-network-label-wrap-length 20))

Org-roam-server uses an emacs-lisp Web server, and presents you with a unique way to interact with your knowledge lattice. Connections are visible, you can click nodes to view only a subsection of your graph, on hover previews, and more. This is my preferred way of “having a conversation” with my Zettelkasten.

I don’t start the server automatically. Rather, when I want to use it

I M-x org-roam-server, open my browser to 127.0.0.1:8080 and

that’s it.

deft

With the setup above you can capture new notes, and you can consult your Zettelkasten, find a note you may be interested in, open the note, follow links, and basically “have a conversation” with your knowledge lattice.

But what happens if, for example, you remember writing something down but don’t know exactly where you wrote it?

Check the sidebar screenshot again. Let’s say you are researching

something about sharding infrastructure but don’t remember exactly

where you put it, or what was it related to. If you C-c n f you

are presented with a list of topics, but none have the term

shard in it.

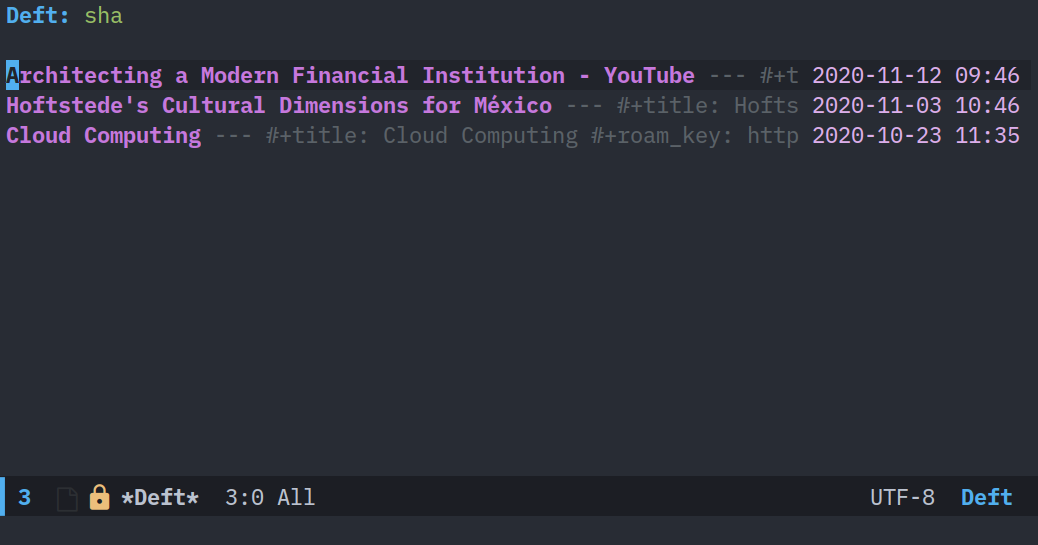

Deft is a full text search engine that we can use for many things, but in our case we’ll use it for searching our notes.

(use-package deft

:bind ("s-F" . deft)

:commands (deft)

:config

(setq deft-extensions '("org")

deft-directory "~/Sync/Org/roam"

deft-recursive t))

We simply point deft to our note repository, and tell it to only

consider files with an org extension, and to search recursively in

case you use directories for organization. That’s it.

Using deft to find notes with the term sharding

Putting it all together

In my note taking journey I struggled to get the whole picture. Explaining the method is a challenge, as the benefits of the system are only made apparent after you’ve spent some time with it and built a critical mass around your notes.

The purpose of this section is to present you with a practical example of how to use your setup in a real world scenario.

Suppose you are getting started on your work day, and your boss sends you a link to an article. You open the article, pen and paper at hand, and start reading.

As you progress through the article you make some throwaway notes, with some tidbits about why you think it’s important, where in the article it’s located, and how it might relate to other topics.

When you are done reading, you hit your bookmarklet and a new note is

created for you with the title and roam_key property already filled

to the article’s URL.

At this point you can either spend the time converting your throwaway notes into permanent notes if you have time right now, or you can simply save the empty note that you will use later in the day to “translate” your throwaway notes. I usually take this second approach.

Later throughout the day, you open up your empty note created earlier, collect your throwaway notes about the article, start org-roam-server and open up your Zettelkasten. You are ready to have a conversation with it.

See your existing notes. What do you see? how is this new article relevant to your existing knowledge? how does it connect to existing notes?

Ask these and other questions as you translate your throwaway notes into your permanent notes. Create links, either to existing notes, or to new empty notes. Linking to new (empty) notes serve as a reminder of topics that need further research.

As you link this article’s note, you may realize of a connection that is not readily apparent. For example, as you read through an article related to the SaaS model of software delivery, you may realize that key performance indicators (KPIs) are not only important for APIs (you already knew that), but also to measure your customer’s growth. This is not explicitly mentioned in the article, but you make the connection thanks to earlier research into service level agreements (SLAs).

This is all made up, and a concrete example of why it’s so hard to explain how to use the Zettelkasten method, but hopefully you get the idea.

Conclusion

My journey to note taking was backwards. I never knew I needed something better than my existing system of keeping a notebook with me at all times while I work (but not whenever I read).

I’m a heavy user of Org Mode, and eventually stumbled upon Org-roam. Wanting to expand my Org Mode use, I configured it without knowing what to expect. It wasn’t until I read the book How to take smart notes that it all clicked together and saw how inefficient (or rather, nonexistent) my current note taking system was.

The practical case outlined in Putting it all together is based off of a recent experience I had. It honestly felt I had superpowers, and I was free to concentrate all my brainpower on making the relevant connections and generating insight, instead of remembering long read facts.

Hopefully you can have note taking superpowers too.